INTERVIEW: David Jackson talks about Ilya Repin, a major painter of Russian society

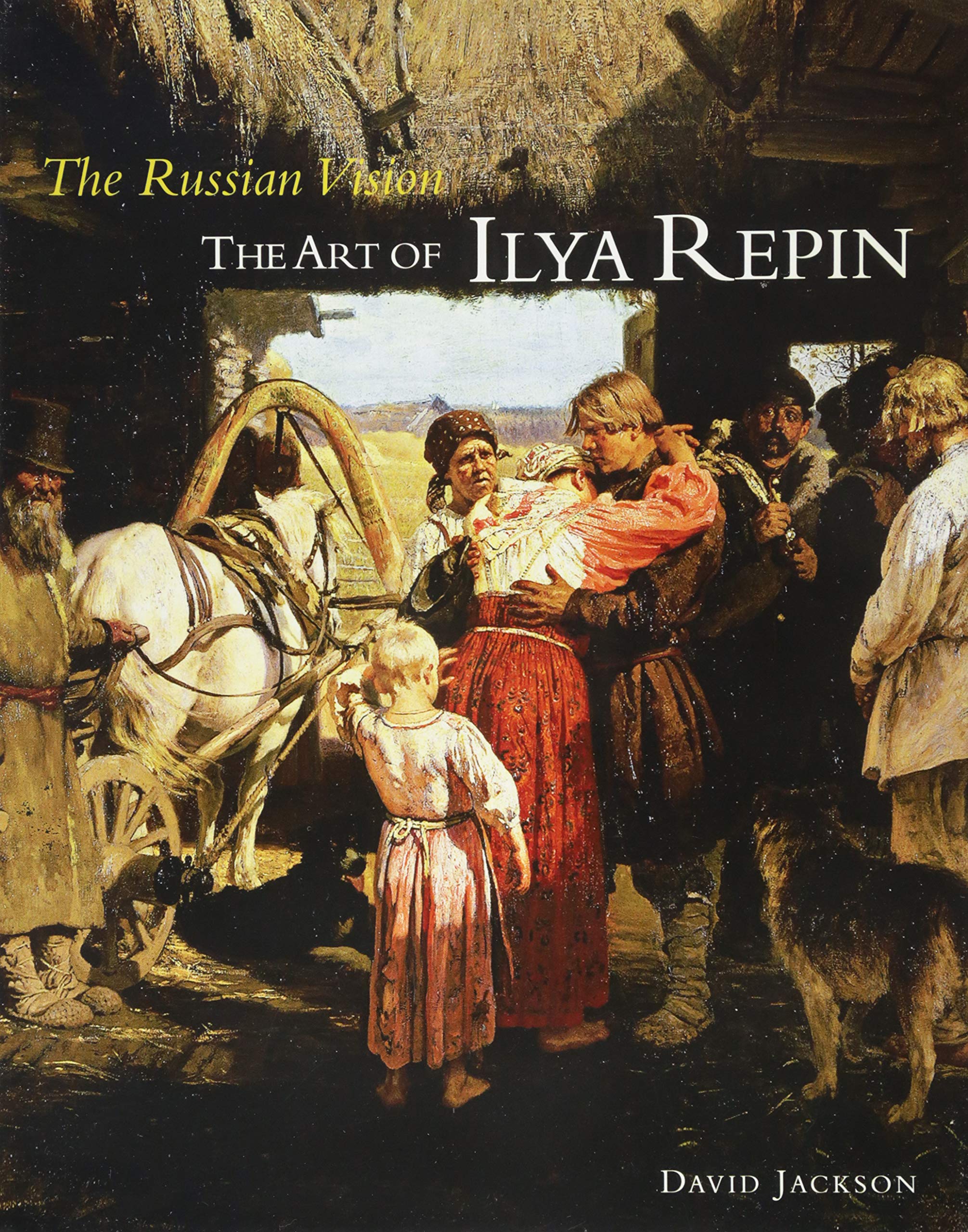

David Jackson is Professor of Russian & Scandinavian Art Histories at the University of Leeds. He works principally in the fields of nineteenth century Nordic, Russian and Soviet art, with teaching interests in the cultures of Classical Greece and Victorian Britain. In the past decade he has curated exhibitions for many major institutions, including the National Gallery, the Scottish National Gallery, the Van Gogh Museum, and the Swedish National Gallery. He has published on 19th century Russian realism with particular reference to the works of Ilya Repin and is the author of The Russian Vision: the Art of Ilya Repin (BAI, 2006; Antique Collectors’ Club 2014) and The Wanderers and critical realism in nineteenth century Russian painting (MUP, 2006; 2011). Anna Prosvetova, Deputy Editor of Russian Art & Culture, talked with David about Ilya Repin’s art and life and and his place in Russian art history.

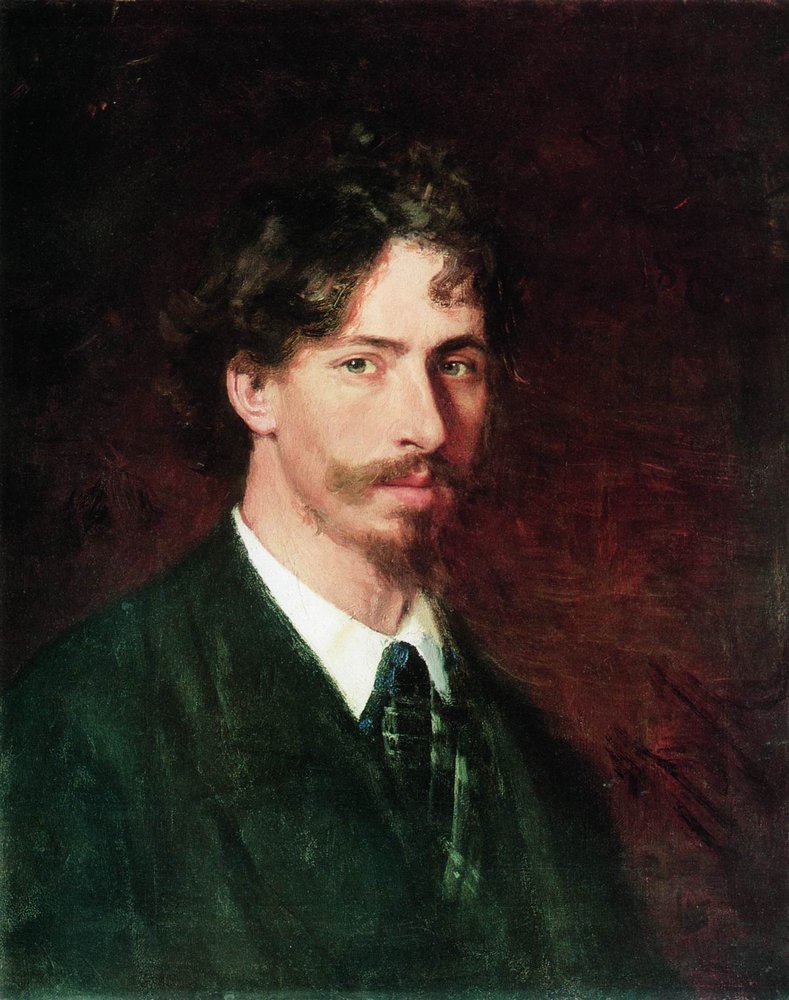

Ilya Repin, Self-portrait, 1878 / Courtesy of The State Russian Museum

Anna Prosvetova: Could you tell us more about your recent book on Ilya Repin and why you think he is considered such an important Russian painter?

David Jackson: The book was first published in 2006 and it went out of print quickly. This time I have managed to get another publisher, Antique Collectors’ Club, who also published books on Isaak Levitan and other Russia-related things. They produce very good books of a high quality. I told them that since the previous edition of the book is out of print, there is really a demand for it, and they decided to publish it. I have updated some information in the recent edition based on the latest publications on the subject.

I think Repin is becoming much better known in the West than he was before. When I published my book in 2006, he was very unknown. I have seen exhibitions happening in European cities over the last few years. When I gave a book launch in London in December 2015 I asked the audience how many of them know this artist, and nearly all the hands went up! I think he is much better known than he used to be. If you look in dictionaries of art, the Oxford Dictionary of Art, for instance, he is there, though back a decade ago he was not there.

The Peredvizhniki or Wanderers have always have been important for me, and Repin, I think, is the best painter of the Peredvizhniki. I know it is my personal opinion and other people would say Levitan or Serov, but for me he is the best among them, the most famous and most prominent, most internationally-known figure. I think for me the importance of these painters and Repin is that they really address Russia. It is not just pretty pictures; it is about culture, politics, human lives: the whole social cross-section of Russia from the aristocracy down to the peasantry. When I teach it to students, they always ask me in the end of 10 or 11 weeks undergraduate module on the Peredvizhniki: “How could we not have heard about these painters?”. I am teaching art history, but none of this makes sense to students until they engage with the social history and culture. It was not just a group of artists working in a little area of a town or some people in a colony on a tip of Denmark. It is the whole social panorama and you see this even in a work like The Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880 – 1833). Here you have every representative of class, profession, and you can literally see Russia in one canvas. Repin is hugely important, I think, in that respect. You could show him to a historian, to an art historian, to a cultural historian, you can deal with his topics from the political point of view – there is nothing he does not cover.

Ilya Repin, Religious Procession in Kursk Province, 1880-1883 / Courtesy of The State Tretyakov Gallery

Ivan Kramskoy, Head of an Old Ukranian Peasant, 1871 / Courtesy of The Museum of Russian Art, Kiev, Ukraine

AP: You wrote your PhD on the art of Ilya Repin. What first attracted you to writing about Russian art? What was an inspiration behind this book?

David Jackson: Yes, my PhD was on Repin and this book came out from that research. I supposed the reason of my interest in Russian art is the curiosity. When I was an undergraduate student, I was doing art history course in the university. I accidentally saw a portrait of a peasant by Kramskoy, just a head, nothing else, and it was such an arresting work. Every hair was painted, every wrinkle in the eye. I have never seen anything like it. I started to look up Kramskoy and at that time I found nothing. I could not google the Internet, I had to go to books, and the books had nothing. The more I looked and the more I found I could not find anything the more I got curious and interested. I went to my teachers at the university and said that I would like to do something around Russian nineteenth-century painting. They replied that there is no such thing, it does not exist. There are only icons in Russia, and then the Avant-Garde and then they do not have anything else. I found this such a strange response, that I started to look myself and made a trip to Russia when it was still under the Soviet Union. I went to look at the Tretyakov collection and the State Russian Museum. The more I saw the more I thought it was fascinating.

After I have done my Bachelor’s degree, I have decided to do some research myself, so I did a PhD. I had to do it in a Russian department, there were no art historians, who could supervise me or had that knowledge. I had to find a Russian specialist in Britain, who would supervise me. It is like everything in life: the more you cannot find, the more you are interested in that. This is similar to what I said in my introduction to the book: the problem in the West is that if these artists are not known, you cannot see them, and they cannot become known. It is a Catch-22, which goes round and round. Thus, you have to keep publishing books and making exhibitions. For instance, we made a Russian landscape exhibition at the National Gallery in London in 2004, and it was phenomenally successful.

I think for me the thing with Russian art is that as long as you show it to people outside of Russia, they would love it, really love it. But you have got to get them to see it somehow, that is the challenge. I have never heard anybody looking at a Russian landscape or Repin painting and say: “Well, it does nothing for me.” People like these works, and it is quite fascinating to watch.

AP: Could you tell us more about your research process? Did you face any problems doing your research in Russia as a Westerner?

DJ: I did not have problems, because even when I went in the Soviet period, Repin and the Peredvizhniki were much loved by the Soviet regime. For the wrong reasons, but nevertheless, they were considered good art. If during the Soviet Period I would decided to look at Avant-Garde painting, I would expect problems, but in my case I did not have any. People at the Tretyakov gallery and Russian Museum were very welcoming. The Perestroika period gave me problems only because things went into a bit of chaos. During the Soviet period I had my visa, I did my research and everything was fine, but during the Perestroika I found it hard to get visas and travel. There were some interesting parts to that research. When I tried to look at Repin’s Royal portraits, I was very politely told they were not accessible at the moment. The Soviets did not want me to see the images of Nicholas II or Alexander III, because the Soviet line was that Repin was a sort of Socialist painter of the peasantry. There is Repin’s Emperor Alexander III Receives Village Elders in the Courtyard of the Petrovsky Palace in Moscow, 1886, in the Tretyakov Gallery. It is a huge work in a most incredibly beautiful frame with all the different coats of arms of the provinces and regions of Russia. I really wanted to see this, but I was never allowed in the Soviet period: either it was rolled up or it was somewhere else.

Ilya Repin, Aleksander III receiving rural district elders in the yard of Petrovsky Palace in Moscow, 1886 / Courtesy of The State Tretyakov Gallery

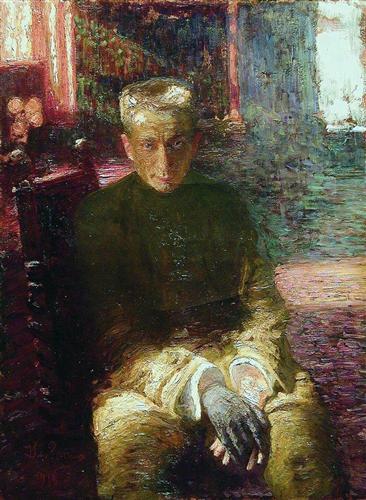

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Alexander Kerensky, 1918 / Courtesy of Wikiart.org

One of the funniest things that I have found, and it is very typical of Russia, was that their focus was much more stronger than in Britain. When I said that I was doing a PhD on Ilya Repin and I had to explain who he was, people would say: “You are doing a thesis on one painter? Not the whole school, just one painter?” For people in Britain it sounded too strange, too narrow. When I went to Russia, and I spoke to art historians there, particularly in the Tretyakov gallery, they said: “Are you writing on all the Repin work?”. They thought that to do a thesis on all Repin’s life and work is too much.

AP: You have been researching Repin and the Peredvizhniki for many years. Could you share one or two stories from Repin’s life that impressed you most?

One of the most interesting things I have found was that during the time you are researching, works of art keep coming to the surface in the places like Christie’s and Sotheby’s; things that were lost or were not known around. I remember very interestingly this portrait of Alexander Kerensky that came up for sale. I have interviewed some very elderly people who have been around at this time, the time of the Revolution itself, and we started to uncover some of the aspects that were contrary to what the Soviet Union was saying. Repin was both for and against the Revolution. He thought the Revolution was good in the sense of it answering the needs of ordinary people, starving people; the sort of things that precipitated the shooting of 1905. But when he found out about how the Soviet regime was culturally iconoclastic, when they destroyed churches, for instance, he was very critical of it. This is of course was not published and was not known. I think he was very good, very consistent as a humanitarian. Repin was for the politics of Lenin, he thought that it was ok, but the practice of those politics was not right. I thought that was interesting.

One should remember that Repin was a peasant, he was emancipated as a peasant. He grew up as a child being somebody’s property, with no real education in the university sense, but he was very articulate about these things. I think it was interesting to find out that he had been critical of the Soviet regime, while all the books would tell you that he was a pure Socialist painter. In the West a part of the Repin’s problem has been that because he was an artist approved of by the Communist regime, that made him in the West automatically a bad painter. They have swallowed this propaganda, but he was much more fascinating figure than that.

The Penates, the Repin House-Museum in Kuokkala, now Repino / Courtesy of Wikipedia

Among other interesting and amusing things I have found was that when he had the house at Penaty on the Gulf he had a very strange lifestyle, which I have always found fascinating. He slept outdoors, on a balcony, even if it was covered in snow. When he had visitors, they had to do everything for themselves, there were no servants. He also imposed his vegetarian regime on everybody. I would be happy with it, I am a vegetarian myself, but they did not like it. There is a story that a little railway station down at the Penaty did a very good trade in meat sandwiches, because everybody who left Repin’s house and came straight to the railway station were desperate for some meat. He also did some eurythmics and had ideas about healthy living. He set some sort of Gandhi regime with strict vegetarianism, and when the war came and the borders closed, he could not find enough food and had to eat fish. He said that he felt deeply morally reluctant by this activity, but he had to do it to survive. His lifestyle was so eccentric in that sense and many people commented on it. I could imagine how people such as Vladimir Stasov, a respected Russian critic, had to do a morning exercise while the gramofon records played, but Repin insisted that everyone should be involved in it.

Overall, the thing that came out of that research most was that Repin is exceedingly versatile artist and a man, whose opinions changed and developed. He is a complex person, but he was being presented in Soviet literature as a very narrow one with just one focus in life. The West accepted that and spent a lot of time in the Cold War, talking about the Communist propaganda, but we believed every word they said, without questioning it. Poor Repin became a victim of the Cold War politics, where one side cast him as a proto-Communist, and the other side would believe it. He is a very rich and very complex character, and I think that comes out in his art.

AP: Repin spent a great amount of time working and exhibiting in Europe, being influenced by its artistic scene. Could you tell us more about this period of his life?

DJ: He spent some time in Europe as a student, and then later on he travelled around Europe with Stasov and went to some of the big capitals. Repin was somebody who was deeply interested in art and why people make art. Whenever he travelled, he was fascinated to go to the museums, to see what other people were doing, even things he did not like. One of the things I wrote about and found very interesting was that there was a part later in his life when he gets involved in this very public debates with the young avant-garde like David Burliuck and others. He comes out very strongly for old-fashioned, salon academic figurative realist art and condemns the Avant-garde as being rubbish. Repin was not a very public persona and what is not shown is that very soon after that he, Burliuck, Mayakovsky and other Avant-Garde artists got together. They all come to Penaty to have lunch, and they sit and chat about art. Here Repin is completely confused about why he would think that drawing a triangle or a square is art. But he is fascinated why somebody would think this way. For example, when he is in Europe, he is aware of Monet and Impressionists, and he is not sure whether there is the right way forward, but he is aware and conscious of what is going on. When he is in Madrid with Stasov later on, he is fascinated by Velasquez and he had always been a great admirer of Rembrandt and the great masters.

Ilya Repin, Unexpected Return, 1884–1888 / Courtesy of The State Tretyakov Gallery

There is a theory that his second visit to Paris did affect his art. When you look at a work like The Unexpected Return, 1884-88, you can see the brightness and the application of paint is much more of a contemporary French manner than of an academic Salon manner. I think there is may be some truth in that. Repin was a great devourer of art, even in magazines and similar things he was fascinated to see what people were doing. Even when he did not like an artist, he was still fascinated to learn why the artist painted or thought like this. He was really driven by art, as some people are driven by drugs, he just could not stop. Every day of his life he could not stop painting. When he got old and his hand withering, he should have stopped on health grounds, and his family tried to stop him. They took his paints away, and when they came back from a walk one day and found that the artist dipped a cigarette in an ink well and painted on the wall. So, they gave him his paints back. I think that I have finished the book with this Repin’s quote, when he said that he loved art like a drunkard, he could not stop.

AP: David, how would you describe your main audience? Who are you writing for?

DJ: I would like to think that I am writing for everybody. I guess I know that specialists in art history, people who are interested in Russian culture are likely to find the book first, but I tried to write it in an accessible manner. I do not presume my reader knows Russian culture or art history, and I try to take people through these things. It is a very much of a cultural history, may be even more than art history. I am aware that if you write a book like this, you cannot just discuss it like an art historian, if you know that you will have so much information that your readers do not know. That is always the case with the Peredvizhniki as well: you cannot show Myasoedov’s The Zemstvo Dines, 1872, if they do not know what zemstvo is. I guess it is going to be Russophiles, students, art lovers… But I am hoping after that the word of mouth might work. I discovered with the exhibitions we did, for instance, with the show on Repin in Holland in 2002, which just blew up in their faces; it was a phenomena. Some people were telling other people to go and see this show. In the introduction to this book I have written about a Dutch person living in England, who got a call from her friend, who told her to come back to Holland to see this exhibition. When she asked why, the friend replied that Repin paints portraits as good as Rembrandt. For a Dutch person to say that is outrageous. People were taking extra trains up to this northern Holland place and it broke the box office.

Grigory Myasoedov, The Zemstvo Dines, 1872 / Courtesy of The State Tretyakov Gallery

I think Repin speaks to everybody. The main challenge is getting people to actually see his work. Once they see him, they are hooked. I would hope the book would be interesting to everybody, I tried to get away from a lot of jargon and from the presumption that my reader is an art historian or a Russian specialist.

AP: If you would have to choose, what is your favourite painting by Repin? DJ: This is a very difficult question! I would like to answer with a little anecdote. When I have done the exhibitions and worked on this book, I have never select a cover. I am so close to this material, I know it so well, so I forget what it is like to see it brand new. I have said to the publisher this time that they should choose the picture cover for the new edition, the one they think is really good.

Ilya Repin, Barge haulers on the Volga, 1873 / Courtesy of The State Russian Museum

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Baroness Varvara Ivanovna Ikskul von Hildenbandt, 1889 / Courtesy of The State Tretyakov Gallery

I guess for some sentimental reasons I still think that my favourite works are The Religious Procession in Kursk Province and The Barge Haulers on the Volga, 1873. But I think the most favourite is The Religious Procession. It was one of the first pictures that really lighted up my imagination. It has more colour, different layers of the class and society, and festivity of this big religious procession. You can spend hours in front of this picture with the students, pointing at every little detail in it. I remember the first time I looked at it I really wanted to know what is going on there. The same with Unexpected Arrival, but it is a very serious work, it is hard to have it as a favourite. These are that type of pictures that really pushes your interest. You can look at the Barge Haulers with a great sympathy, and even if you know nothing about that picture, you can feel for these people.

I know many people prefer the society portraits, for instance, Portrait of Baroness Varvara Ivanovna Ikskul von Hildenbandt, 1889. It is very beautiful work and I understand why people like it, but for me The Religious Procession is still the most significant work by Repin.

AP: Your research interests are connected with Russian and Nordic art and culture. What are the stylistic similarities in the works by these artists?

DJ: It is very similar from the stylistic point of view. The great Nordic painters, including people like Edvard Munch, as well as the great Russian painters, are very concerned with addressing their own culture, but for that reason they are not too worried about style. Today we think that art history is only about style, but it was not always like that. This is an interesting difference between the Soviet painting, which says: “Progression is not about style, it is about content; about what you show, not how you paint.” Today in the West we disagree, but in the nineteenth century you will find most nations and most cultures were trying to establish their identity through their art. Nearly all of them used a Salon-based realism, which owns a lot to Jules Bastien-Lepage. It uses a loose brush technique, but when you stand back you see a very solid, realistic representation. One of the interesting things in Nordic and Russian art is that when you get close to Repin or Anders Zorn, you see that it is painted quite roughly, sketchy, but when you stand back you see this solidity, hardness.

When I first went to Scandinavia it was to look for Russian paintings, mostly in private collections in Stockholm. I was struck when I was looking at Nordic things there, which were very similar to Russia, but the stories they were telling were not familiar to me, because now they were from the Nordic culture. I tried to think about that when I wrote the Repin book. When I first look at Nordic culture, I knew very little, so how would I know how to look at these pictures, I needed some help. I thought to myself: “Let’s presume that people who are opening the Repin book have not seen the work, who are not familiar with it. They will look at a picture and think that it is interesting, but then they will need to know what is going on there.” Nordic art is the same: it addresses social problems, life of ordinary people; it stops finding its subject matter in Rome, Paris or the Alps, turning to its own culture to see what is there. That was the strength for me.

Anders Zorn, Self-Portrait, 1907 / Courtesy of Malmö Konstmuseum

Of course, there are also liaisons between artists. For instance, Zond and Albert Edelfelt worked in Russia, and Repin is well-known to work down at Kuokkala in Finland (now – Repino, Russia). Because of the geography, there are crossovers in art too. Repin found himself living in Finland for a while when the borders changed in the First World War and the Revolution. I think it is just the similarity of artists, who want to say something about their own culture.

What the readers also really need to think about is modernity. We look at all these pictures today and think about art history, the past, but all of these painters are painting the modern world. They are not doing it in a modern style that we think of, but nearly everything Repin painted, apart from a few history pictures, is about contemporary modern art, about current affairs.

AP: What are your future plans? Would you like to write more on Russian art?

DJ: At the moment I am not sure. There have been talks about doing another exhibition in Stockholm, because the Peredvizhniki show was so successful. We have got ideas for that and we know what we want to do, but Russian and Swedish governments are not the best friends at the moment. As you may know, there was a Marc Chagall exhibition, that collapsed, and this sparked the whole debate about immunity of artworks. Until the Swedish and Russian governments come to an agreement about what happens when a Russian work of art goes into Sweden, I do not think there will be anymore exhibitions. I am not planning to write about Russian art at the moment, because the exhibitions I am working on now are taking up my time up to 2018.

AP: Thank you, David! We are looking forward to your new exhibitions and publications.

Buy the book on Amazon here.

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.