INTERVIEW: Irina Starkova on her first solo exhibition Still Lives at Erarta Galleries London

Above: Gotta Learn to Fly / Courtesy of Erarta Galleries London

Born in Moscow, 1987, Irina Starkova currently resides between London and Monaco. She studied painting at the Andriyaka Art School in Moscow between 2001-2006, and also worked with the Russian artist Boris Parkhunov. In 2015, Irina was one of 50 artists out of 3,000 entries to be selected for the Winsor & Newton Painting Prize for her self-portrait in oils. She started exhibiting her work in 2013 and has since taken part in the Christie’s Auction in Port of Monaco, exhibited in London’s Commonwealth Gallery, Griffin Gallery and Rossotrudnichestvo in London. We met with Irina at Erarta Galleries London to talk about her current solo show Still Lives and and the research behind the artworks on display.

Golden Eagle with halo (red+blue) / Courtesy of Erarta Galleries London

Anna Prosvetova: Irina, congratulations on your solo show! Could you tell us more about how it came about?

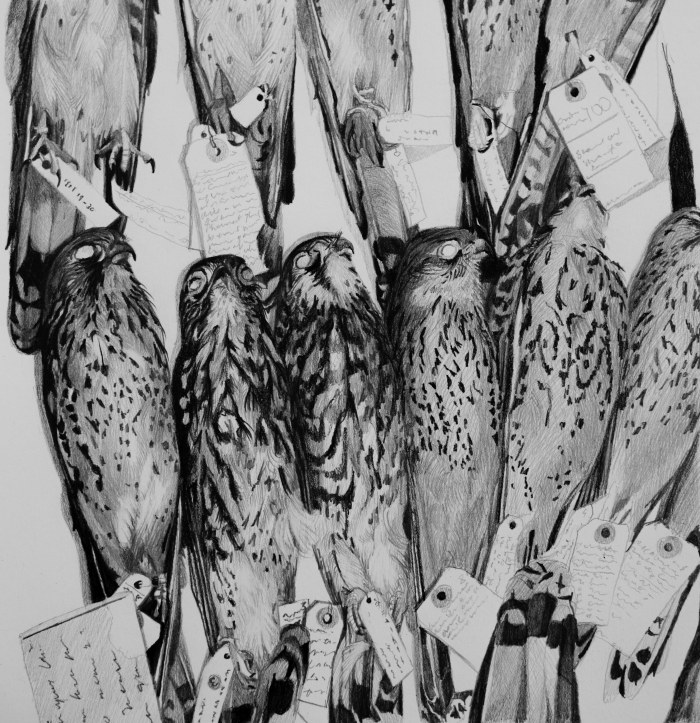

Irina Starkova: This exhibition was inspired by my visits to the archives of the Natural History Museum and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. I got access to the bird archives, where they have hundreds and thousands of physical examples of different birds. They even have some birds’ skins from the 1700s, when explorers brought them back to England from exotic countries. There are still some of those examples, and the feathers of birds preserved so amazingly well.

There were certain things that jumped out at me while I was studying them, and the eagle was one of the striking examples. The person who runs the bird department gave me a key and told me: “The predatory birds are on floor six, exotic birds are on the first floor”, so I was going through those dark corridors and it was like Night at the Museum movie. There were drawers upon drawers of these birds, and I got to the eagle. When I opened it up and carried this golden eagle in my hands to the div I thought it was such a surreal and wonderful experience. That is why this eagle became an emblem of the show. I also think it is a symbolic image, that is why I have added the golden circle, a religious element to the pieces. I guess the main thought behind it is how animals have shaped the human world, how we constantly borrow their forms and re-use them in our world, consciously or unconsciously. The eagle is a symbol of canonising of the dead and creating saints from martyrs. I guess it can be seen as a sinister or a comical thing.

AP: Did you know that you will do it about birds or you just wanted to explore what they have in the archives?

IS: I wanted to explore. My main interests were in ornithology and entomology, and I was visiting both the bird and insects archives. There was something fascinating about the way they are preserved. I used to spend my summers at dacha, catching butterflies and had the most amazing collection. We used to have so many different vegedivs growing there, which used to attract all sorts of amazing butterflies. It was a stem from there, this weird fascination. The birds as well. I used to pick up the birds from a fallen nest at dacha and make new homes for them and raise them. I guess this is probably where it comes from. It has always been an obsession.

Fight or Flight / Courtesy of Erarta Galleries London

AP: You also have self-portraits in this exhibition. Could you tell us more about them and their place in the show?

IS: The main idea behind the portraits is how we appropriate those animal forms. There are elements of metamorphosis, rejuvenation and revival. We do not change our own skin, like a snake, but it is about ways of physical change. I wanted to reflect certain states that I was going through with the help of application of honey, sand, paint or butterflies onto my face and to see how it will work. I guess the whole concept behind the portraits is similar to the exhibition in general – still-lives. Or still lives. It is a play on that word, the leaving and the dead, but it is meant to be in a transient, still and calm sense. The portraits themselves are confronting enough, so I thought it is better to depict it in a meditative state. If you have your eyes closed you can be sleeping, dreaming, or meditating.

The choice of colour is interesting too. I think blue is a symbolic representation of calmness. There are elements of colour with the red sand and yellow butterfly, but overall I wanted to use this blue palette.

Sketch of kestrel skins at Natural History Museum / Courtesy of the artist

AP: The works on display are quite diverse. What are the highlights of the exhibition in your opinion?

IS: There are some of my sketches that I have made form the archives, for instance, an example of trays that they had in the Natural History Museum archive or some specimens from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. They have this amazing collection of antique insects and various creepy creatures. I was fascinated from the beginning! There is another interesting piece in the exhibition,Operational Bugs, talking about how actual forms of the insects themselves resemble everyday objects. Is it conscious or unconscious? I do not know. it is like a chicken and an egg situation.

Here is the most recent work, Aviary, a combination of all the sketches that I did during my research. You can see that some characters form other works on display are present here: the owl, the parrot, the kookaburra. I wanted to do an all-encompassing peace with all the birds.

I think my personal favourite would be Fight or Flight, me and the bird, kookaburra, that self-portrait. For me this work encapsulates the themes of the show I have mentioned – the relationship between people and nature.

AP: How long did it take you to complete the project?

IS: I think it was around a year or ten months of work, but I have already done a lot of the research before. I went around archives here in London, in Barcelona, France and I had a mental picture of what is going to look like.

AP: How long does it take you to create an artwork?

IS: I think some of them could take a couple of months, but there were intervals in between. I work on rotation: while one work is drying, I am working on another one. With portraits it really depends: it can go very well or there can be something that I will not like at all. Once it works, I can work on it for ten hours straight. I listen to so many audio books and radio while I paint, that it makes my head spin. I just finished listening War and Peace and Anna Karenina by Tolstoy.

Operational Bugs / Courtesy of Erarta Galleries London

AP: Could you tell us more about yourself? What is your background?

IS: I am a classically-trained artist. I went to Sergei Andriyaka watercolour school in Moscow from 2001 to 2006. It was a very classical education, when you start with still-lives, drawing one egg, then you have two eggs of different colours and you have to distinguish the colours, using only pencil. It all progressed from there, and I worked with a Russian artist, Boris Parkhunov. He taught me how to create portraits. From there it developed and I was doing a lot of portrait commissions; portraiture always interested me.

I have been painting since I could pick up the pencil, and have been drawing since, probably, the age of thirteen. I have been exclusively dedicating myself to art and had a studio for three years now.

AP: What inspires you in your creativity?

IS: My favourites are mainly figurative artists, for instance Lucian Freud, both his personality and his art, I think they go hand in hand. I also like Grayson Perry. He came over to visit us in Cannes, where he was working on a new documentary, and I met him then. He is a real character and I think he is really shaking the art scene in the UK.

AP: Could you describe how your style or your themes evolved throughout your work?

IS: There is definitely a figurative stream to my work. Potentially over time it might become more abstract, but right now I am still very interested in a human form or an animal form, the beauty and the detail of nature.

Aviary / Courtesy of Erarta Galleries London

AP: You have been living abroad for quite a long time, could you call yourself a Russian artist or just an artist? Do you still identify yourself with this cultural background?

IS: I definitely do, I have the Russian spirit in me. I was born and lived there until I was five. I love going back to Russia, it feels like home. I love just being able to speak Russian. I was taught in Russia, so my style has evolved there and I think it is not something you cannot loose easily. My Russian background is very much built into what I do.

AP: What do you think about contemporary Russian art today?

IS: I think there are a lot of amazing contemporary Russian artists. For instance, the Venice Biennial presented numerous evidences through many interesting projects. I think today, with the opening of platforms such as GARAGE Museum of Contemporary art in Moscow, there is a much bigger drive in the city. I really hope that it keeps on growing and flourishing, because there is so much talent.

AP: You are also a professional photographer. How does painting and photography correlate in your artworks?

IS: It is such a wonderful combination. For instance, even when I was in the archives, with photography I was able to capture so much in a short space of time. I think it is a really poignant art form and I want to develop it further in the future. I will wait and see for the next exhibition.

AP: What are you future plans?

IS: Usually when I start a new project, first I build up a collection of resources form newspapers and magazines, and then it progresses in sketches. At the moment I am at the sketch phase for my new project. I have got a sketchbook and going around, jotting ideas and taking everything in.

AP: Thank you, Irina, good luck with your next projects!

Still Lives by Irina Starkova is on view at Erarta Galleries London until 31 May.

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.