INTERVIEW: Gabriel Prokofiev on music in the cinema, Sergei Prokofiev’s legacy and classical music today

Above: The Southbank Sinfonia conducted by Gerry Cornelius perform Aphex Twin at the Nonclassical ‘Rise of the Machines’ concert. Picture © Nick Rutter.

Son of artist Oleg and grandson of composer Sergei, Gabriel Prokofiev is a London-based composer, producer, and founder of the NONCLASSICAL record label and club night. His work is informed by his backgrounds in both classical and popular music, especially his work as a DJ and a producer of hip-hop, grime and electro. Gabriel will join Ian Christie on the 7th July at Regent St Cinema to talk about Alexander Nevsky – the film that re-invented Sergei Eisenstein as a sound film director and established his remarkable relationship with film composer Sergei Prokofiev. We spoken with Gabriel before the event about music in the cinema, Prokofiev’s legacy, his own practice and the place of classical music today.

Anna Prosvetova: Gabriel, in the light of Alexander Nevsky screening this week, how do you see the role of music in the cinema?

Gabriel Prokofiev: I think it is incredibly important, and really affects the emotional reaction from a movie. When you are trying to condense a story into two-hour film, music is the most effective way of speeding up the message and the engagement with the audience. Unfortunately, recently the use of music has become very formulaic, full of cliche, especially in Hollywood film-making. There are many musical devices, that are used to pull certain emotional strings. I find this very disappointing and I wish that more filmmakers would take the risk of working with more closely with composers, who will push the music further. The interesting thing is that audiences like it when the music in the film is more challenging, more interesting. One of the classic examples, is 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968, by Stanley Kubrick, when they used music by György Ligeti and Richard Strauss in the soundtrack. Another more recent example is 2007 film There Will Be Blood with an original orchestral score by Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood. This collaboration of contemporary composers and filmmakers could be happening on a bigger scale, and I am ready to help to solve this situation.

Alexander Nevsky, 1938 / Courtesy of www.acmi.net.au

Today once the film is finished, a composer is sent a rough cut and they have two or three weeks to put together the whole score. When Sergei Prokofiev and Sergei Eisenstein worked together on Alexander Nevsky in the 1930s, they discussed the script, and Prokofiev composed much of the music before they even started filming, and finished it after the shoot. It was a proper collaboration. Now the music in the cinema has taken on a much more utilitarian, functional role, while with a right collaboration it could be more exciting, and I hope we could return to this director-composer closer relationship.

AP: Did you always know that you will be a musician?

GB: No, I did not. People might not expect such answer from me, coming from such a famous family name in the music world. My father, Oleg Prokofiev, was a visual artist, a painter and sculptor, and all his life he was trying to forge his own artistic identity. My grandfather, Sergei Prokofiev, and his music were, of course, present in our household, but we were not living continually conscious of our connection to Sergei Prokofiev. It was not a house full of music, but more a house with visual art; I would say more broadly with art atmosphere. When I was young, I was more interested in becoming an actor, but when I was around eleven years old I started to write songs with my friends. That is when I started to discover my real passion, and it evolved with time. I was choosing between music and the theatre, and music became a more powerful force for me.

AP: I know that you have a classical music education. What attracted you to electronic music afterwards?

GP: That came first, actually. When I was eleven or twelve years old, it was the 1980s, when you had the birth of electronic music. I liked synth-pop and electronic dance music when I was a teenager. I bought a synthesizer and was very interested in using a computer for music. So, it was something I was always interested in. When it came to studying classical music, I had a real passion for composition and I went to university to study music. In Birmingham University, where I first studied, they had a very good department for electroacoustic music, the classical electronic music, and I studied it further there. This was a very good way for me to discover my voice as a composer, with some disconnection from my classical roots. There was no connection with the symphonic work of my grandfather, when I was using electronics to make a big piece of music, therefore, I could develop as an artist.

However, ultimately, I got frustrated with the electronic music, mainly because the live performance of electronic music is often unsatisfying, because a lot of it is prepared beforehand, there is less of communication between the performer and public. When you see an orchestral performance, you can feel the incredible sense of community, energy. Also, as a composer, I felt even more exhausted, because you have to finish the whole electronic piece in the studio. You become the composer, the performer, and the producer, and you have to include a nuance of a live performance in the studio recording. It is great, but I think there are some brilliant musicians out there – why not to write a score and give it to them, so they could bring a new life into it. I am a sociable and communicative person, and I love the interaction between the composer and a performer. I would like a performer to give their contribution to the work; it should be a conversation.

AP: For me composing music is something magical. Could you tell us about your working process or rituals?

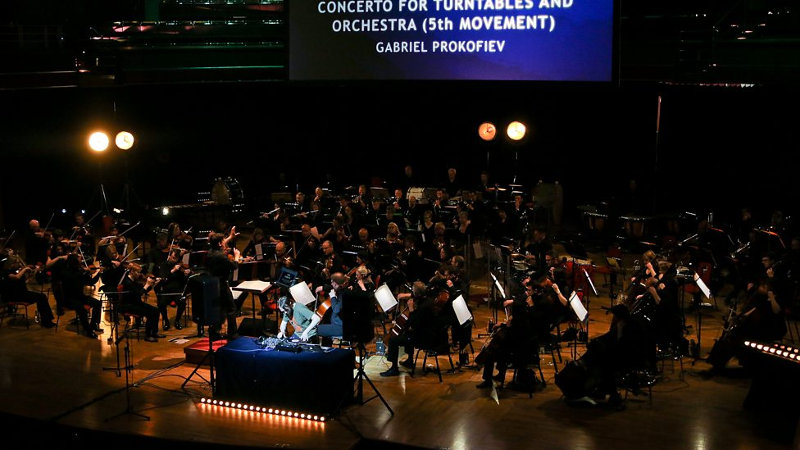

BBC Concert Orchestra and DJ Mr Switch perform Gabriel Prokofiev’s ‘Concerto for Turndivs and Orchestra’ / Courtesy of BBC

GP: I have developed a certain way of working. What is very important for me in music, is to have these core ideas, such as theme, harmonic progression or some interesting sound texture, that would bring a magical energy and natural feeling to it. When I am commissioned to write something, I would start with doing a lot of sketches everyday. Even if I do not want to work or in a bad mood, I just force myself. Once you are in this routine of sketching, you stop worrying about the final result. You tell yourself that if it is bad, you can just throw it away, there is no pressure. It takes a creative mind into a very relaxed state. That is when the magical ideas appear. You are not waiting for an inspiration, you are continually producing your material.

Once I have a lot of sketches, I then turn on a more critical and analytical side of my brain and I go through all sketches and find the ones that have some potential, in my view. Then start to use them as building blocks to create a larger piece. It is quite a straightforward process, but by working like this I can get some ideas that have a natural and instinctive feel to them. One of the hardest struggles in this process is composing the piece together and leaving out some parts. Sometimes I am in love with an idea, but I cannot find a way to make it work in a bigger composition.

AP: You are a grandson of Sergei Prokofiev. Could you tell us how you see his place and contribution to classical music?

GP: Of course, I am biased in his favour. I am very close to his music, and for me his music is a brilliant direction for classical music. There is a strong connection with the past, but also a very original approach and a very distinctive voice as well. It is my personal feeling, but I do think he is very important in terms of the music history. He is a brilliant composer in terms of melody and orchestration. As for his direction, he was one of the last melodic composers in classical music. Shostakovitch was younger and continued this melodic aspect in his writing, but maybe not as much as Prokofiev. After that era classical music got carried into the post-war anti-melody, anti-music, in some respect, and anti-tradition attitude, I think this attitude is less relevant now, but it still dominates in conservatoires and music colleges. My grandfather proved that there could be different paths in classical music, and I think there is an increased interest to his music today and movies he worked on, you can find a part of his legacy is in film music.

Sergei Prokofiev / Courtesy of Wikipedia

AP: Could you say that your grandfather’s music influenced your work?

GP: Yes, I can. Some of my work is quite different, of course, and it is hard to compare, especially when I work with electronics or percussion. I have done lots work that is harmonically more dissonant, more crunchy and syncopated, and thus further from Sergei Prokofiev’s music. However, inevitably there are certain types of harmonic or melodic movements that come up in my sketches and are clearly connected to his work. These ideas are simply inside me, because I know his music so well. When I was younger, I used to censor myself and tried not to sound too much like Sergei Prokofiev, but now I am more relaxed if I have elements in my music that are more Prokofiev-ish. Recently I had a premier of two new caprices for violin and orchestra, and both pieces have an unexpected harmonic shift, which is quite in his style. People in the audience noticed, but I was happy about that. I am happy to be influenced by him, and as I said before, I think his approach is still relevant.

AP: Have you ever thought about remixing your grandfather’s music?

GP: People have asked me this question before. I would say that because of his stature as a composer, it would be a hard work for me to do after trying to find my own voice as a composer. I think if I would start remixing my grandfather’s music, people would not take it seriously. I think it might take precedence over my practice, and I have to keep my distance and focus on my own work. I have done reworkings of some other composers, but even then I am quite careful about it. AP: As you have mentioned, your father, Oleg Prokofiev, was a famous artist. Could you tell us about your relationship with visual art and how did his creative practice influence you?

Oleg Prokofiev, Bodies / Courtesy of University of Surrey

GP: I love visual art and I have my dad’s paintings and sculptures around the house, they influence me. I do like to look at visual abstract art; it can be a good stimulus for ideas. I do not have a favourite artist, but I think Russian art, especially the first half of the twentieth century, is so exciting, especially the early abstract work of artists like Kandinsky. I also like works by Robert Falk, my father’s teacher.

I work a lot with dance, where you have a human form and a visual aspect is very important. I would say this is where I have had a strong connection with another art form. I have not done a project directly with a visual artist yet, painter or sculptor, but it is something I would love to explore, maybe doing a series of music pieces inspired by paintings.

AP: What are you main inspirations?

GP: I would say the world around me, my personal experiences and London. I find the city very inspiring. I combine those inspirations with the musicians that I am working for. It is important to know who I am going to work with and who is going to perform the piece. For instance, I was writing a saxophone concerto for Branford Marsalis, an American saxophonist, and in this case my influence was the instrument itself. Saxophone has its life as a jazz instrument, but I did not want to write a jazz concerto, and I started thinking of what is the soul of the saxophone, who is the saxophone? The piece became a fantasy or journey of a rebellious man; a solitary figure; almost a personification of the saxophone. And that brought in social aspects as well. On another side, I have just finished a second concerto for turntables, and for me that was the challenge of what could I do next with that instrument, after I have composed the first concerto for Turntables, and how it could stimulate the audience.

AP: Could you tell us more about your NONCLASSICAL project? How did it come about and how it developed during its twelve years of existence?

GP: It started out of my frustration as a composer. I saw that the audience at classical concerts was quite small and not from my peer group. It tended to be two or three times the age of a composer or a performer. As a young composer, I wanted to share my music and my experiences with people of my age as well as with older people. None of the musicians or composers seem to care about this situation, they just have accepted it. I have been playing in a band in clubs since I was twelve, where we were playing for young people. I thought that if I want a younger audience to hear this music, they are not going to come to a concert hall, because it is not in their lifestyle, so I have to bring it to them, take classical music to clubs and bars, where people feel comfortable. That was the concept of NONCLASSICAL project, and it worked from the first time twelve years ago. We get a nice mix of people of different ages at these concerts.

Recently, we did an Orchestral Club-Night, a big event called The Rise of the Machines, at Ambika P3, a warehouse, and about two thirds of our audience were people between twenty and thirty-five years old, and then other ages. You do not really get this mix at a traditional classical concert, and I think this situation should change. Most people have a ‘well-balanced diet’ when it comes to literature or cinema. They can read a comic as well as a long novel, but for many people an orchestral concert at a traditional concert hall is not a part of their life. In the early twentieth century the world of classical music became more formal, while before it was more inviting for a wider audience. It has retreated into a high-art bubble, which could be seen as a form of protection from the rise of popular culture, but at the same time it can be very damaging. It is especially true for contemporary classical music, and I think it is our duty as composers and musicians to bring it back to a contemporary audience of different ages.

NONCLASSICAL performs Rise of the Machines at Ambika P3 / Courtesy of Ambika P3

At NONCLASSICAL we do monthly events (on second Wednesday of every month) at The Victoria Club in Dalston. These are chamber concerts with two ensembles of contemporary music and a resident DJ. We play music by different composers, including myself, and also do bigger orchestral events as well. NONCLASSICAL now has a very good following, and became a charity.

AP: What is your dream as a musician and composer?

GP: I do not know where to start… To finish our discussion about NONCLASSICAL project, I would love to see it expanding with more events in different cities, because I think there is the potential. I believe it is important for people today to hear not only pop songs or repetitive dance music. As a composer, I am really enjoying composing orchestral music at the moment, and I would like to see it performed more in informal spaces, such as warehouses. There are some great projects out there like The Multistory Orchestra, who performing multistory car parks.

I have done several projects with dance, and I am interested to do more large-scale dance projects. I am going to do something with The Stuttgart Ballet next February. I also would like to work with opera and compose for cinema too. I really enjoy collaborating with other art forms.

One of my definite personal plans for next couple of years is to make an album of a chamber music, with some electronics and live performance, which I can later tour and present to a wider audience. With all the orchestral music I have been writing I have realised that it does not get recorded, because orchestral recording is very expensive to organise. So, you have a few concerts, receive a good feedback, but then nobody else can hear it. Now I have about four years of hard work, which is not available as a recording.

AP: What are your current projects?

GP: I am currently an artist in residence at The Casa da Música in Porto, which is a an amazing modern music venue. They have commissioned me to compose a Concerto for Turndivs n.2, which is going to be premiered by the Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto Casa da Música with Mr Switch, a world-champion DJ. I have just finished it, it was a really exciting piece to compose. It was co-commissioned by Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra in Norway, so we will have our second performance there. Couple of days ago I also finished a symphonic work for the Seattle Symphony, that will be premiered in September this year. It is a big work and I still need to find a proper title for the piece. It is a symphony about people in the city, stories of the city. This work was also co-commissioned by The Royal Seville Symphony Orchestra.

There is also going to be a big event in Saint-Petersburg at the end of this year, dedicated to 150th anniversary of my grandfather’s birthday, so I am planning to go there and present some of my music, may be even do a NONCLASSICAL club event as well.

AP: Thank you, Gabriel! We wish you good luck with your projects and are looking forward to the screening at the Regent Street Cinema.

Please visit NONCLASSICAL’s website to learn more about the project and their upcoming events.

Nevsky at War – Screening of Alexander Nevsky in 35mm Followed by a discussion with Gabriel Prokofiev at Regent Street Cinema 7 July, 7:30 PM

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.