INTERVIEW: Jay Vincze, Head of London Impressionist & Modern Art at Christie’s, on Kandinsky’s ‘Rigid and Curved’, 1935

Wassily Kandinsky painted Rigide et Courbé (Rigid and Curved) in December 1935, marking the second anniversary of his arrival in Paris following the closure of the Bauhaus in Berlin. Estimated at $18-25 million, the painting is being offered from an important private American collection and has not been on the market since 1964. The upcoming sale preview in Hong Kong, London, and San Francisco marks the first time in more than 50 years that the work will have been publicly displayed before being offered in New York sale on 16 November. We met with Jay Vincze, Head of Impressionist & Modern Art Department at Christie’s in London, to talk about the story behind this work.

Anna Prosvetova: Jay, could you tell us the story behind Kandinsky’s Rigide et courbe, 1935? What place does it have in Kandinsky’s oeuvre?

Jay Vincze: This work was painted in 1935, in the very early Paris period. The move to the Parisian suburb Neuilly-sur-Seine with his wife was initiated by the closure of the Bauhaus by the Nazis in 1933. Roughly one can divide Kandinsky’s life and career into these geographical locations, and the Paris period is the last flowering of his art. It was a period, when he started these grand scale, very impressive experiments with form and colour, in the way that he had not really explored at the Bauhaus.

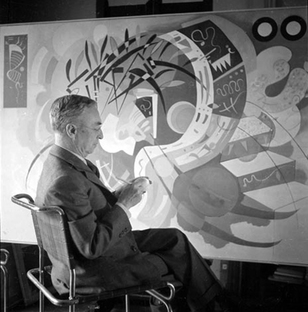

Kandinsky in his apartment-studio in Paris (1939), before 'Dominant Curve' (1936), one of the most representative works of his Biomorphic Abstractions / Courtesy of musings-on-art.org

I would say this work, Rigide et courbe, is without a shadow of doubt, the most important Paris period Kandinsky to come on the market in a generation or two. It holds a unique place within Kandinsky’s oeuvre. Many important works from this period are often in public collections, so you do not see them frequently on the market or in private collections. That is why this is an incredibly exciting piece to come to auction.

The artwork’s history is absolutely fascinating and totally exemplary within Kandinsky’s oeuvre. It belonged to Solomon Guggenheim, who bought it during his trip to Paris the year after it was painted. It was completed in December 1935, and Guggenheim visited Kandinsky’s studio the following year, in 1936, and typed it as one of the great paintings of that period. It entered the Guggenheim collection, and then it was sold in the Guggenheim sale in 1954, where it was acquired by the family of the present owner. Essentially, it had two owners – from Kandinsky through to present day, which is an incredible provenance.

“I would say this work, ‘Rigide et courbe’ is, without a shadow of doubt, the most important Paris period Kandinsky to come on the market in a generation or two.”

AP: What do you think it was that inspired Kandinsky to create this work?

JV: I think the inspirations are many and varied with Kandinsky. He was an all-encompassing artist, he liked bringing in many different influences; he was a very academic man. There are a lot of scientific things going on in this work: these little micro-organisms in rivers and on beaches, amoeba-like characters that fascinated him, or this wonderful creature on the right. This is partly that, which also ties in with the use of sand and texture as well.

Music was an obsession for Kandinsky, right from the early days. The exploration and the links between music and art really find the visual flowering in Kandinsky’s art from the very first moment of abstraction. In this piece you have details that look like bass clefs, and also you have the whole idea of the movement of music, being something that you can reproduce visually. You can really feel that explosiveness of symphonic music, especially in his early abstract years. The work form the Bauhaus period is much more formally structured and rigid, conceptual, and here he is almost returning to those curve-linear forms of the early abstraction.

“Music was an obsession for Kandinsky, right from the early days. The exploration and the links between music and art really find the visual flowering in Kandinsky’s art from the very first moment of abstraction.”

AP: Yes, there is another work in the Guggenheim collection from the Paris period – Courbe dominante (Dominant Curve), 1936. Why do you think he switched from this rigidity of the Bauhaus period when he moved to Paris?

JV: I think it was partly the natural progression. You will find a lot of artists, who work in formal, quite restrictive manner, but at some point they break out into more freedom of expression. You can find the same development in the Pointillism movement, which was very rigidly implied first, and it must have been very liberating to come out of that and give yourself a little bit more of freedom of expression. Perhaps in Kandinsky’s case, the move from the Bauhaus allowed him to explore slightly unstructured compositions and become slightly freer in his forms.

On the other hand, Kandinsky is very often about juxtaposition and contrast. In the very title of the picture you have a contrast between rigid and curved; it is a frequent dichotomy in the titles the artist ascribed to his works, giving some clues to the visual interpretation of them. In a very simple fashion, in this work you have rigid on the left and curved on the right. Kandinsky frequently brings together a lot of different elements within the abstract framework. I think in terms of other influences, there is a suggestion that in a slightly more figurative way the horns in the upper part of the painting could represent the bull and may relate to the subject of the rape of Europa, which was an oft-explored topic through art history.

Wassily Kandinsky, Rigid and Curved, 1935 (detail) / Photo by Anna Prosvetova

AP: In this painting Kandinsky employs an interesting sand technique. What was the inspiration behind this choice? Was this technique characteristic for Kandinsky?

JV: This was something new for his Paris period, very much so. Before he moved to Paris, his works were very flat and plain, one-dimensional. Here we can see a new departure for him, something he was to explore throughout the Paris period. The inception of this idea of using sand to accentuate the surface and give a sense of three-dimensionality to the whole work was such a key feature of that early Paris period. It does create a whole new way of dealing with colour, particularly when juxtaposed against the flat surface. For me, one of the lovely passages is the shape in the top left corner, which is actually quite reminiscent of Matisse, his later cut-outs. Set against that flatly-painted background, it really makes that shape stand out.

AP: In November 2012 Christie’s sold Kandinsky’s Study For Improvisation 8 for a record $23 million. What are your expectations from the upcoming sale of Rigide et courbe in New York?

JV: I think New York is such a global location to offer great works of art, and I believe that Kandinsky does resonate with America a lot, also because the Guggenheim collection is the biggest holding of Kandinsky’s works. In terms of expectation – who knows, these things are never that easy to predict. It is a very different painting from the one we made the world record for, a very different era. This is an area of the market, which I think has not seen as much activity in terms of works coming on to the market, as the Moscow period or the Bauhaus period, for example. The work was extensively toured and exhibited before the sale, and now it is starting its journey to the auction in mid-November. In New York it will be presented during the 20th century week, which covers everything from Monet through to Peter Doig, and we are excited to place it in this chronology as well.

AP: Thank you, Jay! We are looking forward to the upcoming sale.

Please visit Christie’s website for more information about the sale.

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.

Installation view at Christie’s London / Photo by Anna Prosvetova