INTERVIEW: Alexandra Sankova, director of the Moscow Design Museum, on Soviet utopia at London Design Biennale

Above: Team Russia (L-R): PR and development director Olga Druzhinina, Museum’s director Alexandra Sankova, art director Stepan Lukyanov, international relations manager Natalia Goldsteine / Courtesy of Sasha Nikonovich / Moscow Design Museum

Alexandra Sankova is a graphic designer and director of the Moscow Design Museum, which she founded in 2012 together with Nadezhda Bakuradze, Stepan Lukyanov and Valery Patkonen. Previously, she worked as the director of the non-profit organization “New Graphics,” curating various graphic design competitions, projects and events, and as Senior Advisor for cultural affairs at the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Moscow. Since the founding of Moscow Design Museum Alexandra has been the curator and manager of a large amount of exhibitions: Soviet Design 1950-1980’s (2012), Packaging Design. Made in Russia (2013), Common Objects: Soviet and Chinese Design 1950-80’s (2013), New Luxuries: Less + More in an Age of Austerity (2013), Sportcult (2014), Autoposter (2014), Russia. Bread. Salt (2015), Technical Aesthetics (2015), Red Wealth. Soviet Design 1950-1980 (2015). We met with Alexandra to talk about ‘Discovering Utopia: Lost Archives of Soviet Design’ exhibition, curated by her for the first London Design Biennale. The display was recently awarded the Utopia Medal for the best response to the biennale theme.

Anna Prosvetova: Alexandra, thank you for bringing this exhibition to London. Could you tell us more about the project and how it reflects the main idea of the London Design Biennale, ‘Utopia by Design’?

Alexandra Sankova: Four years ago we founded Moscow Design Museum with my colleagues, a group of young designers, architects and design historians. We were very interested in the Soviet design history, because it seemed that there was avant-garde and then a gap after that, when nothing was going on. However, there were many things happening, and the Soviet Union had its own design system, which was very different from the Western one because of the differences in the economic and political situation. This system was supervised by the institution called the All-Union Scientific Research Institute for Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE) with the head office in Moscow and ten branches in Soviet republics, including Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine and others. This Institute also consulted and educated engineers at big factories around the Soviet Union.

The Russian pavilion at the Somerset House / Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

Many projects that were produced by this institution were very futuristic, designers tried to understand how a home of an individual would look like in 50 years; how a personal computer or other electronic equipment would look like. These projects were not commissioned to the Institute by the industry, but by the State Committee on Science and Technology. The majority of these projects had never been realised and put into production. With the help of ‘Discovering Utopia: Lost Archives of Soviet Design‘ display, made possible by our wonderful managing team of Ekaterina Shapkina and Natalia Goldchteine, we wanted to introduce this story and show to the international audience the range of different projects and ideas that came out of this Institute.

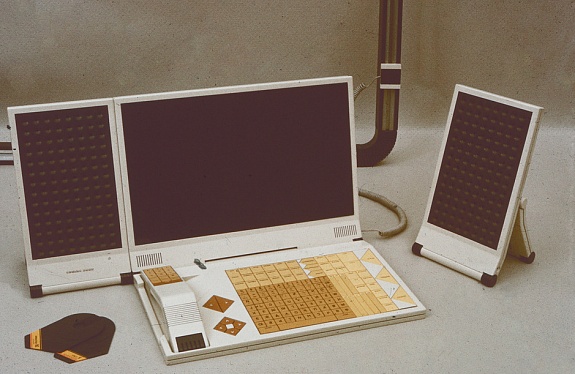

‘Sphinx’ working station The Sphinx station (1987, designed by D. Azrikan in collaboration with A. Kolotushkin and V. Goessen) / Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

Russian history was interrupted so many times that even Russian people do not know the design history of the country. Russian avant-garde is well know outside of the country, with many exhibitions and publications, including works by a historian Selim O. Khan-Magomedov. Today we want to discover the history of the Soviet design and show that design in Russia developed consecutively despite the changes in the political regime, with many interesting episodes and theories. Currently, the major part of the research on the Soviet design is in Russian language, but I believe that with more attention from international experts and designers, this period could find its place in the history of design on the level of Bauhaus school.

AP: Where are the materials for this exhibition coming from?

AS: The institute and its branches were closed after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the archives were lost. The Institute also had the Centre of Technical Aesthetics on Tverskaya street in Moscow, where they showed the best examples of the Soviet design. This centre was closed, and two big tracks with models, received from the Institute’s brunches, were thrown away. However, some materials were saved in private collections of the designers, and later donated to our museum. We communicate with many designers, who worked in the Soviet Union, trying to document and preserve the history of this period. We organise audio and video interviews with them, and for many of them it is their first interview ever. If in America or Europe designers were well known, in Russia no one knows who made, for example, this chair you are sitting on. I could say that all projects produced during this period are good examples of sustainable design, and many people are still using them in their homes.

Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

AP: As a part of the exhibition at Somerset House you are showing a documentary short by director Andrey Silvestrov. Could you tell more about this project?

AS: This movie is a combination of interviews with people, who worked at the All-Union Scientific Research Institute for Technical Aesthetics in the Soviet Union, design historians and practising designers, where they are talking about their work, international conferences and exhibitions. Design exchange with other countries was very active, for example, the first exhibition the Institute organised in Moscow was a show on British design. Later exhibition on Italian, German, Polish design and design of other countries were also organised by the Institute. The film was shot on one of the famous soviet factory – ZIL that manufactured light weight vehicles and trucks as well as the legendary soviet refrigerators. Currently the site has been allocated for new construction and soon the factory building will be torn down. The last filming of this building has been done by us, as a symbol of the bygone age.

AP: Are you planning to produce a publication related to the ‘Discovering Utopia: Lost Archives of Soviet Design‘ show afterwards?

AS: Yes, and for this exhibition we have already produced an extensive booklet in a poster format, where one can find more information about the system of Soviet design and projects produced by the Institute. The very positive reception that the exhibition, designed by our brilliant art director, Stepan Lukyanov, has received from views inspired us to use it for a future project to be shown in Russia. With my colleague Olga Druzhinina, we are currently working on a book of interviews with the Institute’s former designers. We are conducting a deeper research for this publication, trying to find designers from each branch of the Institute, which will allow as to describe not only the system in general, but also the work of each individual branch. We completed our research related to Russia, but it is very difficult to find people who worked in other branches across the Soviet Union, because many of them live and work abroad.

Working on a model of Zil-Sides VMA-30 fire fighting vehicle (1975, designed by V. Aryamov, L. Kouzmichev, A. Olshanetskiy, T. Shepeleva) / Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

AP: Could you highlight some of the projects presented at this exhibition?

AS: Yes, for example this ‘Vtorma design program’. Design program meant that a project could be implemented across the Soviet Union, with several manufacturers involved. The programme presented here was aimed at improving the system of recycling. The designers created a visual identity of the programme, its process, the uniform of the workers and also promotional materials, educating people about the program and how they could be involved in it. They were thinking about how to make the everyday life better, but the industry was not ready for such project, there were no materials and facilities to properly implement it. At the same time, local government did not appreciate such innovation, and therefore, it was never implemented.

There is another interesting project – crafts with underwater fenders. This is a rare example of a project that was produced, and these crafts were also exported around the world, including the UK. Here you can see an archival image of Queen Elizabeth II coming out of one of these crafts.

City equipment for an experimental residential district project developed in 1986 / Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

There is also a project for a fire fighting vehicle, that was designed by VNIITE and sold to France, but they did not produce many copies of that car there. Here is another car project for a Prospective Taxi. It is a small bus with a sliding side door, designed to comfortably transport people in wheelchairs, elderly people and families with baggies. It was implemented as a working prototype, but never got into production. The same can be said about ‘City Equipment for an Experimental residential District’ project. Designers created various equipment for a city environment, including benches, canopy, telephone booths, etc. This project was never implemented, though I think this yellow plastic looks very vivid, and this project could have brighten up Soviet cities, which usually were quite grey and boring.

VNIITE building at VDNKh / Courtesy of Moscow Design Museum

AP: Could you tell us more about Russian Design Day at the London Design Biennale?

AS: This event was designed to bring together experts on avant-garde period, Soviet design and contemporary industrial and fashion designers, who talked about the situation in design industry today. We would like to show the continuity in the development of design in Russia to the international audience here in London.

The program included the such speakers as Konstantin Akinsha, an international expert on the Russian avant-garde, experts on post-war soviet design – Alyona Sokolnikova, Tom Cubbin and myself, Marina Timofeeva, a former Soviet designer, as well as Victoria Andreyanova, a Russian fashion designer, Sergey Smirnov, Russian industrial designer and Anton Stepanov, graphic designer and head of the desing department of a major Russian information agency.

AP: Moscow Design Museum is actively involved in international projects: recently you showed ‘Red Wealth. Soviet Design 1950-1980‘ at the Kunsthal Rotterdam and now represent Russia at the London Design Biennale. Do you have any other international exhibitions planned?

AS: Yes, the exhibition we brought to the Kunsthal Rotterdam will be shown at The Art & Design Atomium Museum in Brussels in 2018. We would love to organise an exhibition in London, but there are no fixed plans yet.

AP: What are your future plans in Moscow?

AS: We are planning to open a Danish design exhibition in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, and ‘Paper Revolution‘ exhibition at Art & Design Atomium Museum (ADAM (Belgium). This show will be dedicated to the centenary of Russian Revolution in 2017 and will be devoted to Constructivism and Avant-Garde graphic design, which this period was famous for. This exhibition will travel to Brussels and may be to Berlin. Soviet Design, 1950-80 will be shown at ADAM in 2018 and we are looking for new locations as we are so exited to tell the story about soviet designers and their works. It is a truly untold story and very important chapter in Russian design history that we hope to share with as many people as we can.

AP: Thank you, Alexandra!

Discovering Utopia: Lost Archives of Soviet Design Moscow Design Museum at London Design Biennale Somerset House, 7 – 27 September

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.